Background: Aging of the face takes on many predictable changes but none is more evident than what occurs along the jawline. The once more discernible and sharp jawline becomes lost as jowls appear and the neck sags. The neck angle becomes more obtuse, the chin may appear shorter, and the transition between the face and the neck becomes obscured. This falling down of the facial tissues over the ledge of the jaw bone into the neck typically occurs due to loss of osteocutaneous ligament support to the skin.

The facelift operation reverses the soft tissue components of this aging process. A facelift is really an isolated neck-jowl procedure that removes fat from the neck, tightens neck muscles (platysma), lifts up the intervening layer of soft tissue between the muscle and the skin (SMAS) on the side of the face, and relocates and removes excess face and neck as it is elevated past the ears.

But often forgotten, and many patients do not see it themselves, is the bony support of the jawline. The strength of the chin and the jawline backs to the bony angles has an influence on how much and how quickly the facial aging process proceeds. Inherently weak chins and a shorter jawline with high mandibular angles indicates a weak system for the prevention of facial tissues from falling over the ‘ledge’ and lack of support to hold the neck tissues up.

As part of any facelift, consideration should always be given to augmenting the jawline. Most commonly, this is seen a simple chin augmentation as weak chins are easy to spot. Chin implant augmentation adds length to the jawline and adds a complementary effect to the restoration of a more acute neck angle. In other cases, an extended implant that incorporates the prejowl area better defines the front half of the jawline.

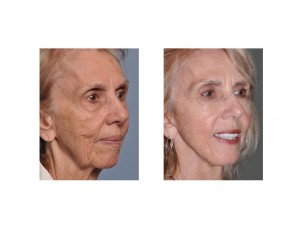

Case Study: This 65 year-old female wanted to improve her saggy neck and jowls that had been slowly getting worse over the past decade. She was a very thin lady with very little subcutaneous fat. She had rolls of skin over the jowls and into the neck with prominent platysmal bands. Her chin had some horizontal shortness and her jaw angles were extremely high, creating a 45 degree angle to her mandibular plane.

Case Highlights:

1) The woman with a short jaw, as evidenced by a small chin and high mandibular angles, will develop considerable neck and jowl soft tissue sagging as she ages.

2) While a facelift is the standard approach to neck and jowl sagging, adding skeletal support through chin augmentation helps recreate a more visible jawline.

3) Chin and jawline implants can be a valuable addition to lower facial rejuvenation.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana