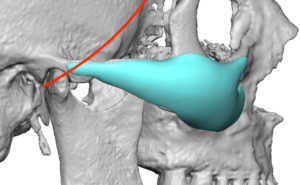

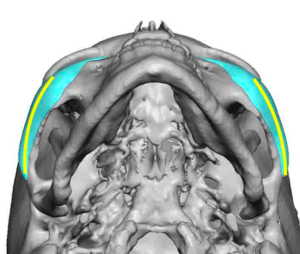

The frontal or temporal branch of the facial nerve courses in front of the ear on its way to the forehead. In so doing it starts deep as it exits from the stylomastoid foramen at the base of the skull and becomes more superficial on its way superiorly through the upper edge of the parotid gland. From this point it becomes more superficial into the upper fascial planes of the face. This takes on great relevance to multiple types of aesthetic facial surgeries that primarily are done around the region of the zygomatic arch. This includes the soft tissue procedures of facelift surgery as well as bone-based procedures such as cheekbone reduction osteotomies and cheek augmentation using extended arch implant styles.

All of these surgeries work in and around the pathway of the frontal branch of the facial nerve and knowledge of its anatomy is important to avoid permanent injury to it. This nerve supplies movement to the frontalis, orbicularis oculi and corrugator supercilii muscles. In essence those muscles that primarily move the eyebrows. Because of its surgical relevance the exact anatomic pathway of this nerve has been extensively studied over the years and reported in many plastic surgery journals. Its pathway has historically been described as following the Pitanguy line from the tragus of the ear to the tail of the eyebrow. (which is defined as running from 0.5 cm below the tragus to 1.5 cm above the tail of the eyebrow) While simplistic in this basic description and assuming the eyebrow has never been modified by surgery or Botox injections, where it lies beneath this line along its course has been the subject of discussion and numerous anatomic studies.

In the May 2020 issue of the Aesthetic Surgery Journal an article was published on this topic entitled ‘A Simple Clinical Application for Locating the Frontotemporal Branch of the Facial Nerve Using the Zygomatic Arch and the Tragus’. In this study the authors used very identifiable and unchangeable surface landmarks, the cartilaginous tragus of the ear and the bony zygomatic arch. In over twenty unilateral cadaver faces the nerve was dissected out and measured to these two anatomic landmarks. Their findings were that the mean distance from the apex of the tragus to where it crossed the inferior border of the zygomatic arch was 3.2cms +/- 5mms.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana