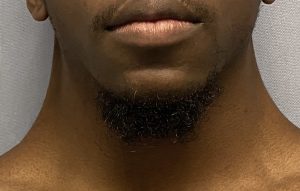

Background: The webbed neck is a well known congenital deformity that appears as bands of loose skin along both sides of the neck. Anatomically it is more than just skin, the neck webs also consist of a widened trapezius muscle as well. Such neck webs are most commonly associated with Turner and Noonan syndromes. But they can also appear in patients who otherwise have no other symptoms or genetic evidence of a syndromic basis for them.

While neck webbing does not cause any significant functional restrictions, some patients may have more limited neck range of motion, it is primarily an aesthetic issue. The traditional approach to their treatment is a direct one with various forms of release and skin z-plasties and/or transposed skin flaps along their line of axis between the ears and the shoulders. While providing reduction of the webs the replacement of scars for the neck webs is for most patients not a worthy aesthetic tradeoff.

A more scar acceptable approach is to move their location to the back of the neck and away from the more visible side of the neck locations. Somewhat similar to lower face and neck lifts, in which one of the goals is to improve/eliminate the central neck sag (band), the incisions are moved to a more favorable location. (ears) The loose sagging tissues are mobilized and relocated back towards the incision location where the excesses can be removed with a more favorable scar result. For the webbed neck this approach may be thought of as a posterior necklift

There are a variety of geometric patterns of posterior excision that can be done in the correction of the webbed neck, all of which avoid lateral neck scars. Shapes such as X, Y and even Z patterns with transposed skin flaps can be done with equally effective results which are perfectly fine in females who have long hair in the back to hide whatever scars are created. But for men the diamond pattern creates a more limited midline vertical scar which could easily mimic the scar from a posterior cervical fusion.

The techniques of midline fascial plication and the quilting of the thick skin flaps reduces the tension on the midline skin closure and lessens the risk of scar widening. They also help support the reduction of the neck webs more than skin mobilization alone.

Case Highlights:

1) The traditional approach to webbed neck correction is to treat the web bands directly but the scars on doing so are not acceptable to most patients.

2) A proved approach to webbed neck correction is a posterior transposition approach that places the scar in the midline at the hairline in the back of the neck.

3) The male webbed neck patient poses greater scar placement challenges due to shorter hair on the back of the neck.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana