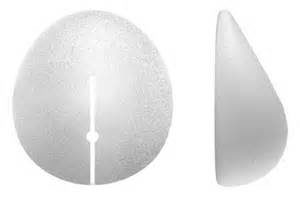

But the use of anatomic breast implants is not without their own disadvantages. They cost more, can potentially rotate postoperatively and require some modification in the surgical technique to place them. They also have a textured coating on their outer shell (to prevent rotation) and can feel more stiff or firm than round smooth breast implants.

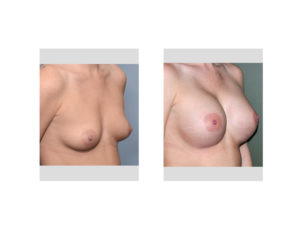

In the March 2017 issue of the journal Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery an article was published entitled ‘Intraoperative Comparison of Anatomical vs Round Implants in Breast Augmentation: A Randomized Clinical Trial’. In this paper the authors looked at 75 primary breast augmentation patients with a round implant placed in one breast and an anatomical implant of similar dimensions and size placed in the other breast. After intraoperative pictures were taken the anatomical implant was replaced with a round one before closure. The intraoperative appearance of the breasts was then assessed by blinded visual evaluations amongst plastic surgeons and lay reviewers.

The study results showed that no observable difference was observed between the two shapes of breast implants in 43% of the cases reviewed by plastic surgeons and 30% of the cases reviewed by lay reviewers. When a difference between the tow sides was observed plastic surgeons judged the anatomical side better in 51% of the cases. Lay reviewers judged the anatomical side better in 47% of the cases. Plastic surgeons identified the correct implant shape in only 25% of the cases. Based on these findings the authors conclude there is no aesthetic advantage provided by anatomic breast implants.

This study is very unique in that it tests how the two different implants look in the same patient. I initially thought the patient was going to be implanted and maintained with two different implants but ths study is understandably limited to intraoperative observations only. On the surface this study provides compelling evidence that anatomic implants do not offer a more natural result than that of round implants.

The most relevant conclusion from this study for me, and what I tell patients all the time, is that the use of anatomic breast implants should be done for compelling reasons. Such implants have some disadvantages that round implants don’t have. Thus their use should be for good reasons such as the patient’s desire to do everything they can to avoid a round breast augmentation result. This becomes particularly relevant as breast implant size becomes bigger.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana