Jaw angle augmentation is most effectively and permanent done with implants. While chin implants have been around for a long time the front part of the lower jaw has different and much more simplistic anatomy than its back part. Thus neither patient or surgeon should confuse placement of chin implants with jaw angle implants which pose more difficult challenges and different risks and complications.

Besides the obvious bilateral or double implant placements needed for the jaw angles vs the single implant for the chin, the jaw angles present more difficult access and limited visibility with the posterior intraoral incisional approach that is commonly used. But the often overlooked but very important anatomic difference between the chin and the jaw angles is in the type of muscular coverage they have. The chin has the mentalis muscle, a muscle largely of facial expression, while the jaw angles have have the masseter muscle, a muscle of mastication.

While the difference in these muscular covers may seem merely descriptive, they offer significant differences int the aesthetic complication risks. The mentalis muscle of the chin originates high on the chin bone and inserts into the soft tissues of the chin in the anterior suibmental region. Thus when a submental incision is made for chin implant placement cutting through the muscle poses no functional issues. The intraoral approach is different as it requires cutting through the origin of the muscle, and while putting it back together poses some risk for postoperative tightness, it causes no risk of of chin soft tissue contour deformation..

Conversely at the jaw angles the goal is to place the implant without disruption of the masseter muscles natural coverage over the bone. (keeping the pteryomasseteric muscle sling intact) If the muscle sling gets disrupted (torn) the muscle will retract superiorly leaving the working end of the implant with only a subcutaneous soft tissue cover. This is the anatomic basis for the well known postoeperative condition of masseteric muscle dehiscence. (MMD) While this does not cause any issues with jaw movement, the soft tissue contour deformity can be a distracting aesthetic issue.

While there are specific factors that can increase the risk of MMD, such as surgical experience in performing the procedure and the type of jaw angle implant, there is another preoperative risk factor that is less well known. Since the insertion attachments of the masseter muscle must be released for proper implant placement, how easy or hard this will be can affect the risk of MMD.

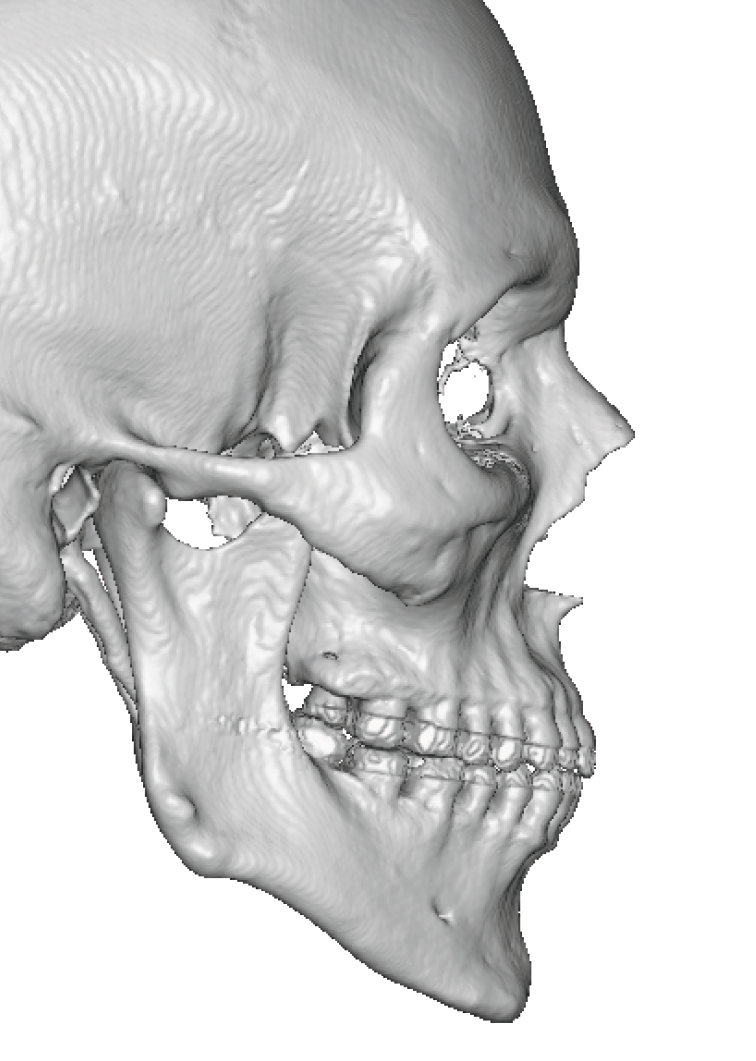

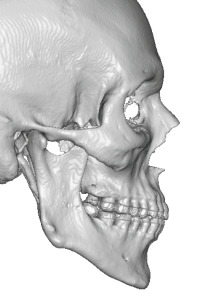

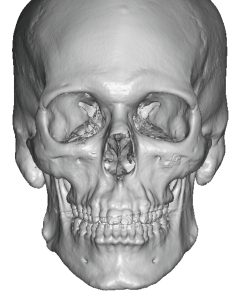

Such bony spikes are not seen on a panorex or plain x-rays and only can be detected on a 3D CT scan. Such scans are an essential part of custom jaw implants designs but not in the use of standard jaw angle implants.

These bony spikes do not mean the masseter muscle can not be released without tearing the sling. But it does provide a preoperative piece of anatomic information that may influence the design of an implant in the jaw angle area, particularly its vertical elongation shape. But at the least they provide preoperative awareness of who is at increased risk for MMD.

Dr. Barry Eppley

World-Renowned Plastic Surgeon