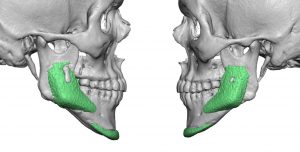

The placement of implants on the facial bones, like implants placed anywhere in the body, causes well recognized tissue responses. The encapsulation of the implant by scar, known as a capsule, is the body’s method of separating ‘self from non-self’. This capsule also serves to lock the implant down, creating a fixed and immoveable implant pocket. This enveloping scar can be surprisingly thick both on the outside as well as between the implant and the underlying bone.

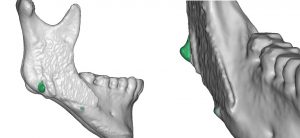

One of the often cited but biologically misunderstood postoperative phenomenon of chin implants, beyond capsular formation, is the bone changes that can occur under them. This bone resorption seen under some chin implants is often viewed as an inflammatory and destructive process. In reality this is a natural and executed biologic response to the placement of a ‘spacer’ between the bone and the overlying soft tissues. To relieve the pressure on the tissues induced by the implant, the bone underneath will allow the implant to settle into the bone a bit. (pressure release) This is a passive and self-limiting process of bone resorption under the implant. It reaches a certain amount and then stops. Why it does not occur under all chin implants is not known.

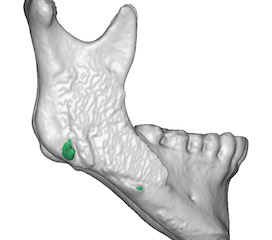

In addition, bone growth is occasionally seen to occur around the edges of some chin implants. In rare cases I have seen the entire implant encased in bone. This is due to a osteoid reaction from the bone lining (periosteum) being elevated and a spacer (implant) put between the bone and the raised periosteum. Why some chin implants have such bony overgrowth while others do not is not yet understood.

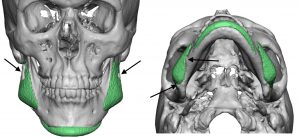

The relevance of these hard and soft tissue changes that occur around chin and jaw angle implants is when revisional surgery is done. The thick capsules will have to be released and some of the bony overgrowths removed to allow for either implant repositioning or the placement of new implants. It is not as simple as often perceived that you can just ‘slip out the old implant and slide in the new one’. Revisional facial implant surgery is often much harder than their initial placement when the tissues are unscarred and more pliable.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana