Background: The mandibular plane angle is a term frequently used in dentistry particularly in orthodontics and cephalometric analysis. Technically it is called the Frankfort mandibular plane angle and is formed by the intersection of the Frankfort horizontal plane and the mandibular plane. These intersecting lines create an angle of which a measurement of 25 +/- 5 degrees would be considered normal. A high plane angle would be 30 degrees or more and a low plane angle patient would be 20 degrees or less. The relevance of this in orthodontics is that a high plane angle is associated with open bites and a low plane angle with closed bites.

But looking beyond the intraoral occlusal ramifications, the mandibular plane angle has external aesthetic facia effects as well. A high plane angle patient can look like they are missing the back part of the jaw with a posterior lower facial deficiency. Conversely the low mandibular plane angle patient usually has a full or prominent jaw angle appearance although the lower face may appear vertically short.

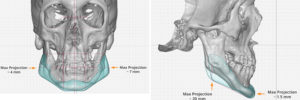

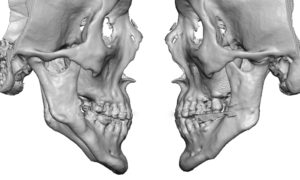

It is the high jaw angle patient that often presents for jawline augmentation. They feel that the jaw angle point is too close to the earlobe or that part of the jaw is absent and gives their face a too narrow appearance. Such a high jaw angle appearance can also result from jaw advancement surgery where the ramus is split into two pieces and re-assembled after the teeth are put into proper occlusion. Such manipulations of the jaw angle bone can result in deformations or loss of part of the jaw angle bone structure.

Highlights:

1) High jaw angles may exist naturally or occur after a sagittal split mandibular osteotomy.

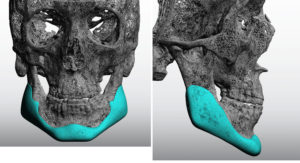

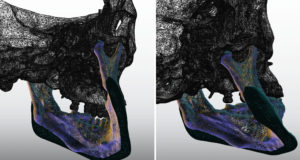

2) Substantially dropping down the jaw angles requires a custom jawline implant approach.

3) The risk of massteric muscle disinsertion is much higher when substantial vertical jaw angle lengthening is done particularly after prior mandibular ramus surgery.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana