The dog ear deformity is a well known phenomenon in plastic surgery. It occurs when at the end of any face or body wound closure a puckering or excess tissue occurs. It is best thought of as a bunching or elevation of skin at the end of the incisional closure. Sometimes it is immediately apparent during the operation and other times it becomes more evident as healing is ongoing and the tissue swelling subsides. It is extremely common in such body contouring procedures as tummy tucks and other long incisional body lifts as well as facial defect reconstructions by primary closure or flap rotations. Its association with the actual appearance of a dog’s ear is a little suspect.

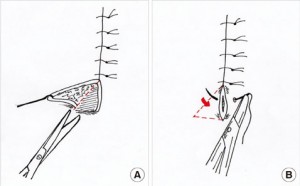

Dog ear wound problems occur for a variety of reasons of which the design and geometry of the tissue excision and closure method is the major contributing factor. Because of its well recognized occurrence, a wide variety of surgical techniques have been devised to eliminate it. Patterns of dog ear excision include various triangles and ellipses of skin. While effective, they all lead to extension of the length of the scar. While for many body areas this may or may not be aesthetically important, it almost always is on the face.

The dog ear problem can be corrected with this technique whether seen during surgery or anytime thereafter. The postoperative dogear problem is one patients are acutely aware of but any correct attempts should be deferred until the incision has settled so the full extent of the dog ear can be appreciated. Most dog ear corrections, which are just small scar revisions, can be done in the office under local anesthesia.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana