Abstract

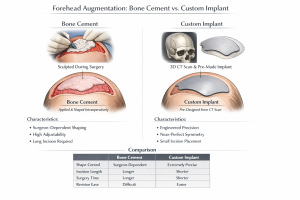

Forehead augmentation is an established craniofacial aesthetic procedure used to alter contour, projection, and symmetry of the upper facial skeleton. Two primary structural methods are employed: intraoperatively sculpted bone cements and preoperatively designed custom implants. Although both techniques provide permanent augmentation, they differ significantly in fabrication method, precision of shape control, surgical requirements, and clinical indications. This article reviews and compares these approaches, highlighting their respective advantages, limitations, and optimal use cases.

Introduction

Aesthetic forehead augmentation addresses congenital or acquired flatness, concavity, asymmetry, or insufficient projection of the frontal bone. Historically, bone cements represented the sole option for structural forehead augmentation. Advances in three-dimensional imaging, computer-assisted design, and implant manufacturing have since introduced custom implants, allowing for greater control over forehead shape and volume. Understanding the distinctions between these two techniques is essential for appropriate patient selection and optimal aesthetic outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Bone Cement

Custom Implants

Shape Control and Precision

Both techniques can achieve satisfactory aesthetic outcomes; however, the degree of predictability differs.

Bone cement allows real-time intraoperative modification but is inherently surgeon-dependent. Symmetry and contour accuracy are generally good but limited by manual sculpting. Custom implants provide near-perfect bilateral symmetry and precise replication of the planned design, with minimal intraoperative variability.

Indications

Bone cement is best suited for:

- Mild to moderate frontal flatness or concavity

- Subtle convex contouring, commonly desired in female patients

- Minor asymmetries

- Cases managed by surgeons experienced in craniofacial cement sculpting

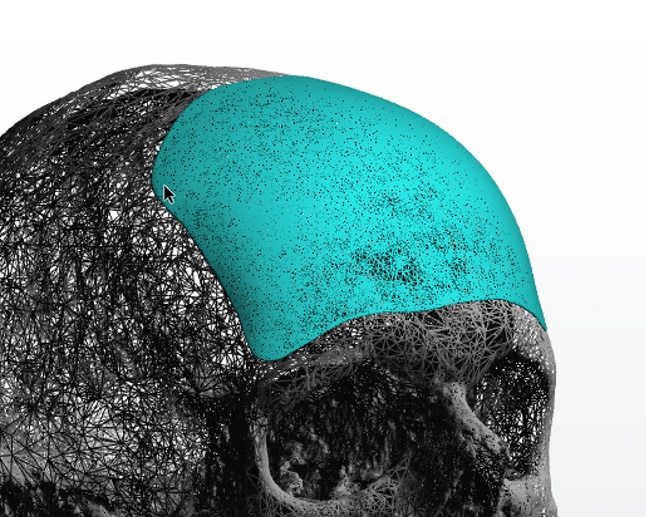

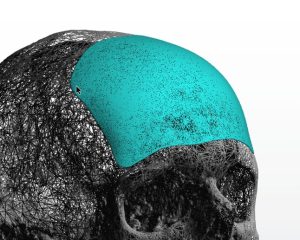

Custom implants are best suited for:

- Significant congenital or structural forehead deficiency

- Posteriorly sloped or retrusive frontal bones

- Specific contour requirements, including brow ridge projection

- Large surface-area augmentation

- Cases requiring maximal symmetry and reproducibility

Surgical Considerations

Operative time is often longer for bone cement procedures due to sculpting requirements, whereas implant placement is more time-efficient once the implant is manufactured.

Recovery and Outcomes

Postoperative swelling and recovery timelines are similar for both techniques, with most patients resuming normal activities within 10–14 days. Final contour stabilization typically occurs by approximately three months postoperatively.

Risks and Limitations

Bone cement carries an increased risk of contour irregularities, asymmetry, and difficulty with revision or removal once fully integrated. Custom implants allow easier revision or replacement but require greater upfront planning, higher cost, and preoperative manufacturing time.

Discussion

A common misconception is that bone cement represents a more “natural” augmentation due to presumed osseous integration. In craniofacial applications, PMMA functions as an onlay implant rather than a biologically integrating material, forming a fibrous interface with bone. Thus, its classification as “bone cement” is a historical artifact derived from orthopedic usage rather than a reflection of cranial biology.

This does differ from hydroxyapatite bone cement (HAC) in which bone does bond directly to the synthetic material. But HAC has more difficult handling and shaping properties, requires a far more open scalp incision, does not set well if the recipient site is not very dry and has high costs associated with it.

Conclusion

Dr. Barry Eppley

World-Renowned Plastic Surgeon