Background: Manipulation of the frontal sinus cavity is an essential part of brow bone reduction surgery. Removal of the outer table of the frontal sinus bone, reshaping of its osseous form and replacement back over the large exposed underlying sinus cavity are the essential elements of the procedure. While it rarely is a problem, the devascularized reshaped bone segments over the frontal sinus go on to usually heal uneventfully. This occurs even though much of their surface area has no direct bone contact and its underside s exposed to the passage of air coming up from the nose.

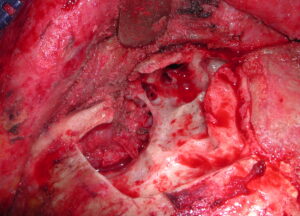

Should infection of the bone flap occur in brow bone reduction surgery, however, the bone is quickly lost and the overlying forehead contour collapses inward. The bone flap has little resistance to infection being largely avascular and very thin. Antibiotics can be effective for controlling the infection but elimination of bone infection requires generous debridement back to vascularized tissue and the bony sequestrums removed.

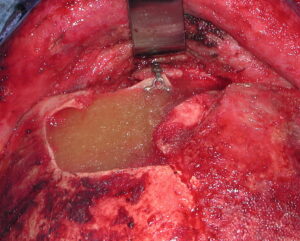

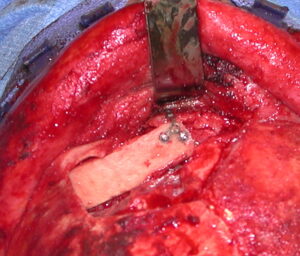

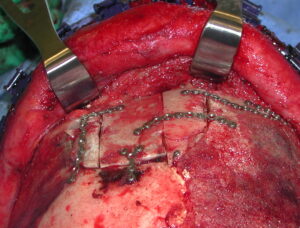

Effective reconstruction from brow bone infections must incorporate three main principles. Creating a permanent separation of the nose from the frontal sinus, a complete fill of the frontal sinus up to and including the desired forehead contour (frontal sinus obliteration) and the use of autologous bone grafts to do so.

Case Study: This middle aged male had a prior history of brow bone reduction surgery for another part of the country four months previously. He developed swelling of his forehead and nasal drainage beginning at three weeks after surgery. He was placed on antibiotics, including intravenous varieties, which got his infection under control. But over the ensuing months he developed an increasingly deep lower forehead depression with some intermittent nasal drainage.

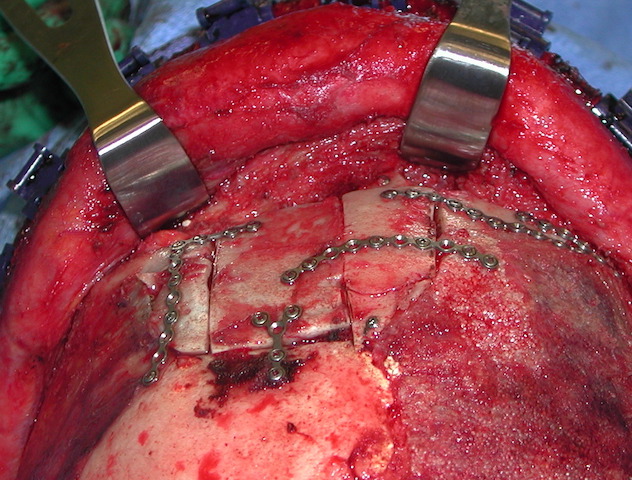

Reconstruction of an infected brow bone reduction site requires debridement and obliteration of the entire frontal sinus cavity with bone grafting. Split thickness cranial bone is the best donor source and a convenient one. It require a generous harvest for adequate graft material. Fortunately this type of complication from brow bone reduction is very rare but it can be adequately resolved.

Case Highlights:

1) Frontal sinus infections after brow bone reduction can lead to osteomyelitis with open communication to the nasal cavities.

2) Aggressive debridement of frontal sinus bone and permanent elimination of the nasofrontal connection and frontal sinus cavity is essential to infection resolution.

3) The skull provides an ample source of bone graft material from the outer table which can be generously harvested for obliteration of the frontal sinus cavity and restoration of the forehead contour.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana