Background: In placing a chin implant there are two approaches, intraoral and submental incisional access. Each has their advantages and disadvantages. What is most obvious to the patient is that the intraoral approach avoids an external scar with a somewhat higher risk of infection. The submental approach has a lower risk of infection but at the tradeoff of an external scar.

On the surface that appears to be the major distinctions between the two…but it isn’t. There is one major difference, and it can have a significant impact in certain patients, and that is in how each incisional approach affects the mentalis muscle. The submental approach disrupts some of the insertion areas of the muscle while the intraoral approach disrupts the bony origin of the muscle. That seemingly innocuous difference should not be under estimated. In the right patient under certain circumstances the impact of the incision on the mentalis muscle and the overlying soft tissue pad can have adverse aesthetic consequences.

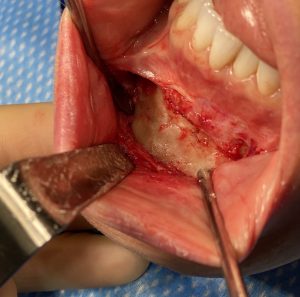

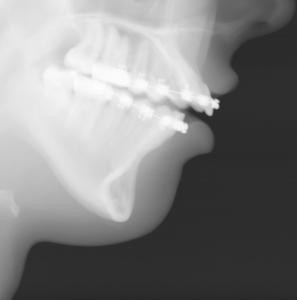

Under general anesthesia and prior to making the incision, the depth of her lower vestibule and the residual midline scar was seen. In preparation for a shortening vestibuoplasty during closure, the mucosa of the depth of the vestibule was initially excised on both sides.

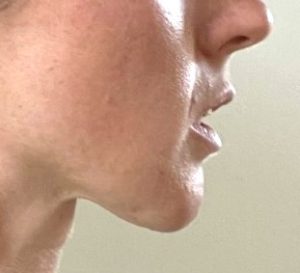

The intraoral chin implant placement approach does disrupt the most important end of the mentalis muscle…its fixed bony origin. In the face of infection and inflamed tissues the removal of the chin implant does not allow for proper soft tissue resuspension. Once healed secondarily the entire chin pad falls of the end of the bone dragging down the lower lip with it. This adverse sequelae is magnified in the shorter chin with a backward sloped chin bone.

Case Highlights:

1) Chin implant placement and subsequent removal, particularly when done from an intraoral approach, has an increased risk of soft tissue deformities.

2) Loss of soft tissue chin pad attachments, particularly the origin of the mentalis muscle, results in ptosis, lower lip incompetence with excessive tooth show and a deep vestibule.

3) The combination of a sliding genioplasty with mentalis muscle resuspension, grafting of the bony step off and a shortening vestibuloplasty can help restore the soft tissue chin position on the bone.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana