Introduction

Sliding (bony) genioplasty is a well-established technique for chin augmentation. Its main advantage is that it uses the patient’s own bone, avoiding the need for an implant. However, it has drawbacks: the bone cut can be angled in multiple ways, the resulting chin may take on an unnatural bony shape, and revisions are more complex than with implants. Additionally, it carries its own set of complications, including inferior border stepoffs, a deepened or tight labiomental fold, hardware palpability or irritation, bony asymmetries, and—rarely—chronic bone pain.

Traditionally, the osteotomy cut is obliquely oriented, beginning higher in the midline and angling down toward the inferior border. Once the segment is freed, dimensional adjustments can be made. Early fixation relied on wire ligatures, where the segment was slid forward and wired to the superior cortex—hence the term “sliding” genioplasty. While effective, this technique permitted only horizontal movements. Today, plate fixation is preferred, as it allows for greater flexibility in repositioning. Regardless of fixation, reshaping of the chin bone alters the inferior border and labiomental fold, sometimes producing visible irregularities.

Although the thick chin pad often camouflages these changes, certain patients experience problematic secondary effects.

Case Study

-

Inferior border stepoffs (more pronounced on the right)

-

Tight labiomental fold with lower lip retraction

-

Submental chin retraction

-

Chin asymmetry

-

Chronic chin pain and numbness

-

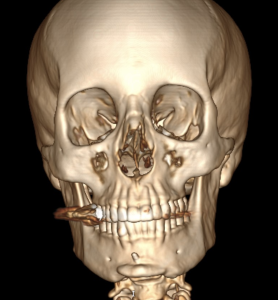

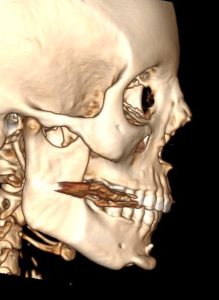

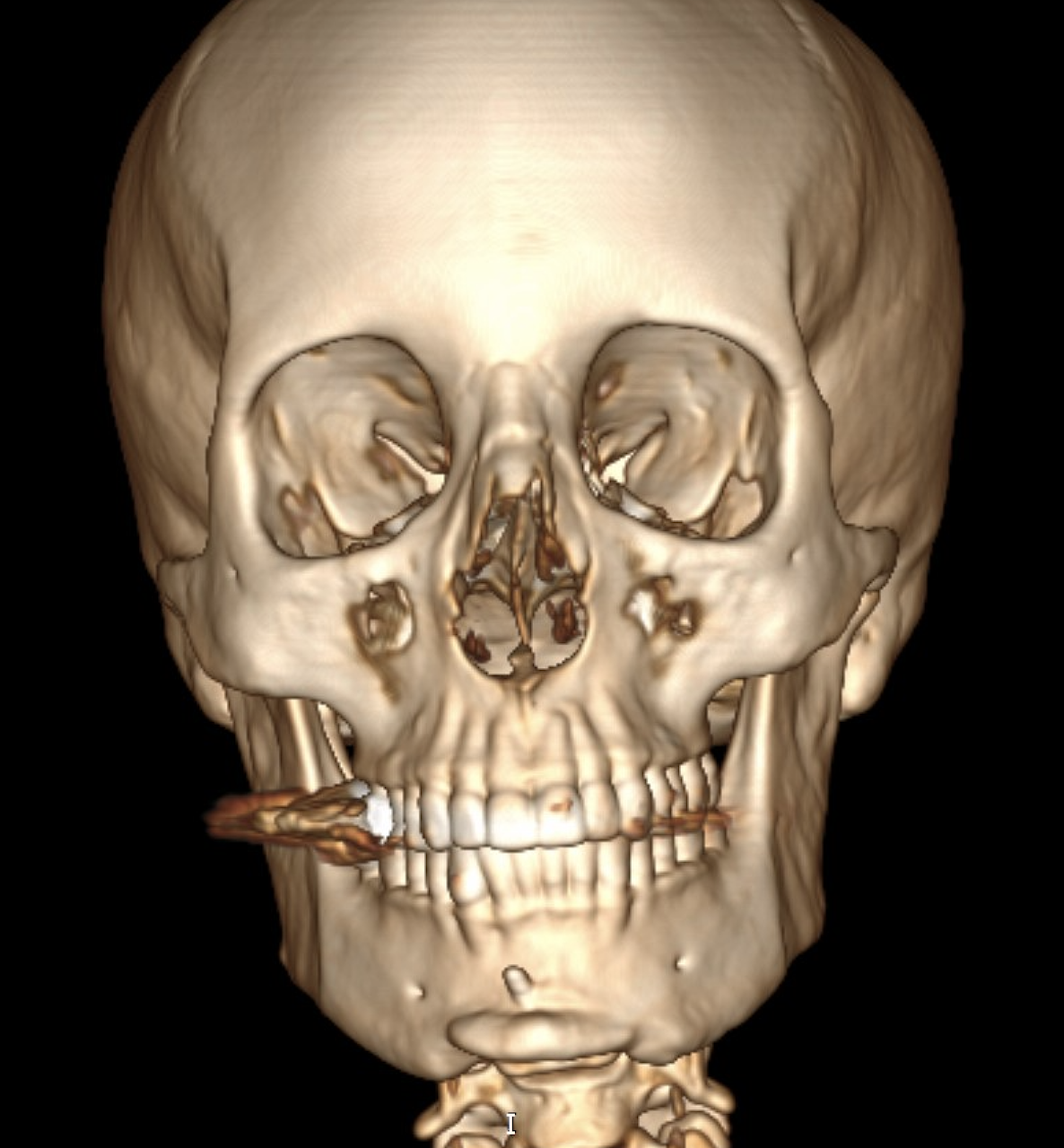

High-positioned bone segment from the genioplasty

-

Prominent wire ligature

-

Multiple inferior border irregularities (right side larger)

-

Bony asymmetry of the chin

Operative Findings and Management

-

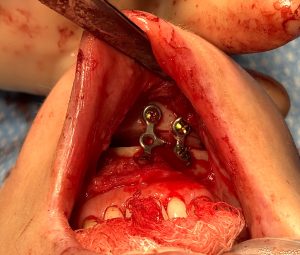

Right inferior border stepoff: Reduced with an inferior border shave, accounting for the asymmetry.

-

Bone grafting: The resected bone was used as an interpositional graft, repositioning the chin 2–3 mm downward and slightly leftward. Double-plate fixation secured the segment.

-

Allogeneic bone chips: Placed into residual gaps and irregularities for smoothing.

-

Soft tissue management: A dermal-fat graft was added between incision and bone to fill dead space, reduce contracture, and provide volume.

Discussion

This case illustrates how bony deformities after sliding genioplasty are often dictated by the osteotomy design and fixation method. A steeply angled cut, combined with wire fixation, tends to elevate the segment, compressing the chin pad and creating discomfort. The exposed wire tail itself may also be symptomatic, particularly in patients with nickel sensitivity.

By lowering the segment and removing the wire, decompression of soft tissues was achieved, aiming to relieve pain. The patient’s natural asymmetry magnified the inferior border deformity, which required both shaving and grafting.

Correcting chin asymmetry through genioplasty is notoriously challenging, as repositioning often generates new irregularities. Using the resected inferior border as a bone graft provided structural benefit while minimizing waste.

For patients with tight lower lips and scarred vestibules, release alone rarely resolves symptoms. Reintroducing soft tissue into the dead space—whether as dermal-fat or other graft material—is often essential. Although graft resorption is a risk, particularly in secondary procedures where bone vascularity is reduced, the potential functional and aesthetic benefits justify its use.

A sliding genioplasty can be a very effective procedure with a low risk for complications when technically well performed. However when attention to the details of the osteotomy cut, bone repositioning and hardware fixation are overlooked or are unknown a cascade of aesthetic and functional symptoms can arise that requires a far more comprehensive procedure to resolve and that of the initial surgery.

Conclusion

-

Prominent fixation hardware can be a significant source of postoperative chin pain.

-

Sliding genioplasty is rarely the ideal approach for correcting congenital bony chin asymmetry.

-

Inferior border shaves can be repurposed as graft material in revision genioplasty.

Barry Eppley, MD, DMD

World-Renowned Plastic Surgeon

Right inferior border stepoff: Reduced with an inferior border shave, accounting for the asymmetry.

Right inferior border stepoff: Reduced with an inferior border shave, accounting for the asymmetry. Bone grafting: The resected bone was used as an interpositional graft, repositioning the chin 2–3 mm downward and slightly leftward. Double-plate fixation secured the segment.

Bone grafting: The resected bone was used as an interpositional graft, repositioning the chin 2–3 mm downward and slightly leftward. Double-plate fixation secured the segment. Allogeneic bone chips: Placed into residual gaps and irregularities for smoothing.

Allogeneic bone chips: Placed into residual gaps and irregularities for smoothing. Soft tissue management: A dermal-fat graft was added between incision and bone to fill dead space, reduce contracture, and provide volume.

Soft tissue management: A dermal-fat graft was added between incision and bone to fill dead space, reduce contracture, and provide volume.