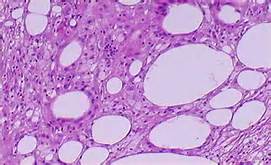

Fat injections have become a widely used cosmetic procedure for a variety of aesthetic facial concerns. Fat grafts are viewed as safer than any other injectable material since it is an extract of the patient’s own tissues. Despite its safety fat injections are not perfect and they are prone to aesthetic complications of which irregular contours (lumps and bumps) being the most common. In rare cases with periorbital injections, fat (and any other synthetic injectable filler) can lead to acute visual loss.

In the December 2015 issue of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, an article entitled ‘Periorbital Lipogranuloma Following Facial Autologous Fat Injections: Non-Surgical Treatment’ was published. In this paper the authors encountered twenty-seven (27) patients with periorbital lipogranulomas after fat injections. Interesting nineteen (19) of the female patients were treated with cryopreserved fat. Twenty one (21) of the patients were treated by corticosteroid injections and oral steroids. The steroid injection protocol was 0.1ml of Kenalog 40 initially followed by a second injection four weeks later if not responsive. The oral prednisone dose was 0.5mg/kg for one week which was tapered off over the next month. Resolution was achieved in 15 patients (71%) and partial resolution in 5 patients. (24%) One patient (5%) has no response.

Periorbital granulomas are diagnosed by history and physical examination. CT and MRI evaluations can be done but do not take precedence over a recurrent swollen lump in the lower eyelid after fat injections. This study shows that the first approach should be steroid injections. Surgical excision is reserved for those that have a failed response to non-surgical treatments.

It is interesting that in rare cases fat can create a reaction similar to that of synthetic injectable fillers. I can not help wonder that the use of cryopreserved fat made up a disproportionate number of these cases. This makes a case for not storing and reusing a patient’s own fat for subsequent fat injections.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana