The success of breast augmentation depends on the placement of an indwelling device. While once exclusively done with silicone implants in the 1970s and 1980s, their removal from the market in 1991 made saline implants the primary breast augmentation device. After extensive scrutiny and study, silicone breast implants returned for human use by the FDA in late 2006.

While it has been over 15 years since their highly publicized removal, and extensive scientific and clinical studies have failed to show any proven connection to causing autoimmune diseases, patients do ask today about their health concerns.

When patients ask about safety and medical risks about silicone breast implants, they universally are concerned about the implant rupturing and the material leaking or escaping into their bodies. They can clearly see by looking at an implant that the silicone material is encased in a shell or bag, a surrounding sleeve of solid but flexible silicone membrane. So if the bag gets a hole in it or ruptures, it is easy to envision that the silicone is coming out. It is not hard to then assume that it can go running freely throughout the body.

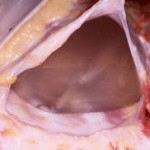

Breast implants develop this surrounding scar that matches its spherical shape, hence the capsule is round and completely encircles the implant. It is usually fairly thin but is quite strong. This is the secondary backup protection to any silicone material that may escape the implant’s shell. Most patients are not even aware that it exists.

Some patients are aware of breast implant capsules when they develop abnormal hardness due to excessive thickening, known as capsular contracture. This is capsule formation gone awry and is not well understood. Fortunately this is not common and its potential occurrence is low when the implant is placed under the muscle. While this is an infrequent negative side to capsule formation, its positive protection function occurs in all patients 100% of the time.

Patient’s concerns about the risk of freely migrating silicone material from ruptured breast implants can be assured that there is a second layer of containment. A breast implant capsule provides a natural shell that will keep any extravasated material close by. When this occurs, it is known as intracapsular breast implant rupture and is interpreted as such on mammograms and MRIs by radiologists. In rare cases, the capsule may also become disrupted, known as extracapsular rupture, but this requires significant force to do so.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana