Aging has an obvious effect on how the face looks from the outside with many recognized soft tissue changes. Wrinkles, deepening nasolabial folds, crow’s feet and jowls are but a few of the effects that gravity and time cause. This understanding has led to the many well known plastic surgery procedures whose intent is to resuspend sagging skin as well as skin removal/reduction.

But much like beauty, aging goes the whole way down to the bone and is not spared. In many ways it is somewhat reflective of what has happened on the outside. Multiple studies in plastic surgery have looked at how the face ages beneath the skin. Volume loss, primarily of fat, creates an overall facial ‘deflation’ and this understanding has led to the widespread use of synthetic injectable fillers and injections of your own fat to help plump up the aging face. But loss of the deepest tissue, the bone, also makes a contribution to this volume.

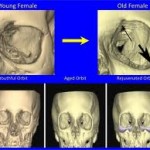

All of these facial bony alterations with age can be correlated to associated outward soft tissue changes. The dropping of the brows and the piling of eyelid skin is a reflection of the loss of underlying bone support. The deepening nasolabial folds and the sagging cheeks are reflective of the maxillary resorption. A weaker chin, jowling and lax neck tissues are partially effected by the loss of lower jaw volume.

The facial skeletion does change with age, primarily with loss of volume of key bony support areas. This results in lessening areas of soft tissue adherence and sagging and deflated overlying soft tissues. This in addition to the loss of facial fat creates the appearance of the aging face.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana