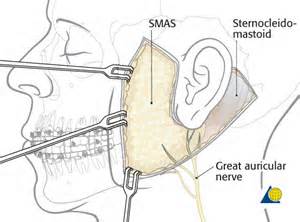

Facelifts are common facial rejuvenation surgeries that are associated with relatively few minor after surgery problems. (e.g., tightness and banding) Many of these issues are self solving with time as tissues heal and relax. One issue that may not improve with time is a nerve injury. While the greatest fear of nerve injury from a facelift is that of a branch of the facial nerve resulting in localized facial muscle weakness, the reality is that this is fairly rare and almost always recovers with time.

Injury to the greater auricular nerve can present in various ways depending upon the mechanism of injury. Stretch or traction injuries result in short-term numbness and tingling. Should the nerve be cut or entrapped by suture, the symptoms will be like a neuroma with a trigger point and radiating pain when touched or compressed. (tinel’s sign)

In the February issue of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, an article appeared entitled ‘ Surgical Decompression of the Great Auricular Nerve: A Therapeutic Option for Neuropraxia following Rhytidectomy’. In this paper the authors reviewed their treatment of four patients who had greater auricular nerve injuries from short-scar facelift procedures. With a positive Tinel’s sign, they underwent decompression of the nerve by stitch removal and an overlay of allogeneic dermis to prevent recurrent scarring to the skin. This led to universal improvement and near resolution of symptoms by six months after the procedure in all patients. This approach was even effective when the time of the original facelift to the nerve surgery was a year apart.

This paper describes a treatment approach for greater auricular nerve injuries that is straightforward and expected. Suture compression was the universal culprit although actual nerve transection and neuroma formation could also be a mechanism of injury. With neuromas, they need to be excised and the proximal end of the nerve buried into the muscle.

What is equally interesting is that all patients in this report had short-scar facelift techniques done with inadvertent suture placement presumably due to limited visibility. (although it could equally be due to a surgeon’s unawareness of the pathway of the greater auricular nerve) While suture entrapment can also occur in more open facelifts, the limited dissection of a shorter scar facelift leaves fewer options for suture placement. In this case, no SMAS suture at all would be better when in doubt as to where the nerve is.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana