Facial implants have come a long way in the past two decades with the introduction of dozens of different styles. One of the expanding facial implant areas is that of the midface. Known commonly as the cheek, it has become recognized that its anatomy is more complex than a single implant design can adequately treat. With the numerous midface implants now available, more patients than ever are being implanted. With increasing numbers of midface augmentations comes complications. The vast majority of these complications are cosmetic in nature, meaning the final result was not what the patient had hoped.

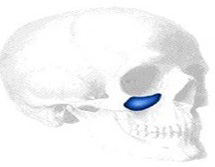

Undesired midface implant results are usually the result of a mismatch between the patient’s aesthetic concerns and the implant type and size. The large number of implant options may seem confusing, but midface augmentation can be thought of as three zones or implant locations. These include the malar, submalar, and suborbital tear trough malar regions. There are more anatomic zones to the midface, but based on desireable facial changes, these three areas can be effectively enhanced.

While these three types of midfacial implants augment areas in close proximity, their effects can produce dramatically different facial changes. Subtle changes in the midface are easily detectable because of their proximity to the eye, a visual focal point in all conversations. The rise in the number of midfacial implants has led to, not surprisingly, an increased rate of complications. Many times the correct zone is augmented but the implant is too big. It is always best to undersize a midfacial implant in most cases. Unless there is a significant facial bone deficiency (e.g., maxillary hypoplasia), large midfacial implants should not be used. What make look like a significant improvement on the operating table can look dramatic in real life afterwards. Other times, the effect the implant created was different than the patient expected. This is most commonly seen with the submalar implant when it is used for a cheek tissue lifting effect and all the patient sees afterwards is unnatural fullness.

The three primary midfacial implants add an effective arsenal to a variety of congenital and age-related midfacial changes. Complications can be avoided by an implant size and type that is suited to the patient’s aesthetic concern. While the midface is one of the hardest facial areas to accurately computer image, such analysis furthers the dialogue between patient and plastic surgeon.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana