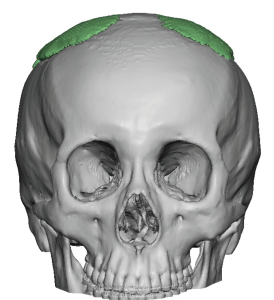

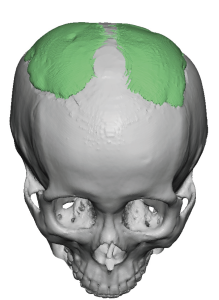

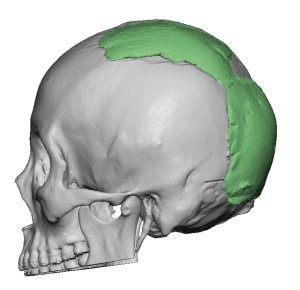

Background: Aesthetic skull augmentations consist of placing various materials on top of the surfaces of the skull to change its external shape. In the history of plastic surgery this skull augmentation material has been PMMA bone cement, one of the few true plastic materials used in aesthetic and reconstructive surgery. While originally intended as a material used to fill in bone defects from lost parts of the skull (usually craniotomy bone flaps) and often called Cranioplast, it has also been used as an onlay material for aesthetic skull augmentation.

While PMMA bone cement can be used effectively in augmentation of the head in properly selected patients, it has significant limitations as an aesthetic material. The major problem with its use is that wide open access through a large scalp incision, where the application and shape of the material can be precisely controlled, is not going to be acceptable in most patients. That is what separates a reconstructive neurosurgery patient from an aesthetic plastic surgery patient. Thus getting a soft putty-like material when mixed through a small scalp incision and then shaping it blindly to the desired effect by external massage has obvious limitations. Irregularities, material edging and asymmetries are common, not the exception.

Beyond shaping issues an often overlooked PMMA skull augmentation effect that is limited is its ability for soft tissue push or displacement. Like any augmentation implant its aesthetic effect is based on pushing the overlying soft tissues outward. Since the scalp is a very tight soft tissue envelope that envelopes the skull the soft putty-like PMMA does not have a great soft tissue push as its sets. As a result its volumetric effect and the amount of skull augmentation is limited particularly when introduced through a small scalp incision. It will be compressed into a thin layer spread out over the extent of the subperiosteal scalp elevation.

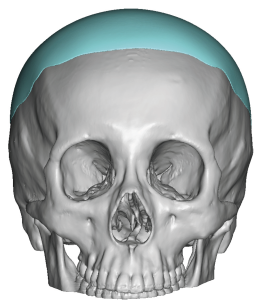

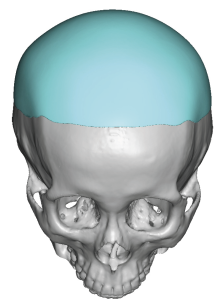

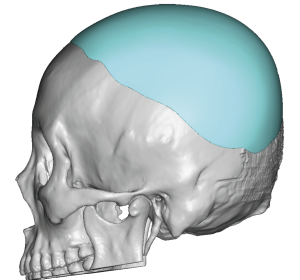

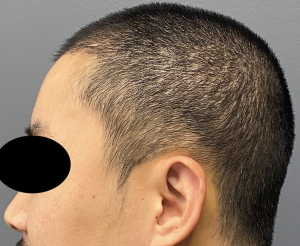

While custom skull implants have some obvious aesthetic advantages, one challenge that still must be overcome is getting it through a small scalp incision. The most common method to do so is to use the elastic deformation properties of a solid silicone implant, usually rolling it for insertion and unrolling it once inside the elevated subperiosteal scalp pocket. But when the size of the skull implant becomes great enough the roll technique will not work unless the scalp incision is made large enough. In this patient he would only accept a scalp incision that was made just a little larger than the one he already had from the bone cement procedure. (which was 4.5cms) We decided that the incision could be extended to 6cms and, if the roll technique did now work for insertion, I would use a split implant technique.

Case Highlights:

1) PMMA bone cement has significant limitations in larger surface aesthetic skull augmentations.

2) Custom skull implants provide superior aesthetic results because of their smooth larger surface area coverages…but can pose challenges for placement through small scalp incisions.

3) The geometric split technique in custom skull implants permits placement through smaller scalp incisions than thought possible given the diameter of the implant.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana