Background

Among the various aesthetic skull protrusions, the occipital knob is the most well-known and visually distinct. As its name implies, it presents as a solitary, rounded prominence at the bottom of the occipital bone, on the back of the head. This structure is an enlargement of the inion, a naturally occurring part of the skull. For reasons not fully understood—though most often seen in men—the inion may become enlarged, develop an exaggerated outward angulation, or both.

The result is an undesired bump that interrupts the natural convexity of the posterior skull profile. In most patients, the occipital knob is due primarily to excess bone. While this creates some associated soft tissue fullness, the volume of soft tissue removal is usually minimal compared to the amount of bone reduction required.

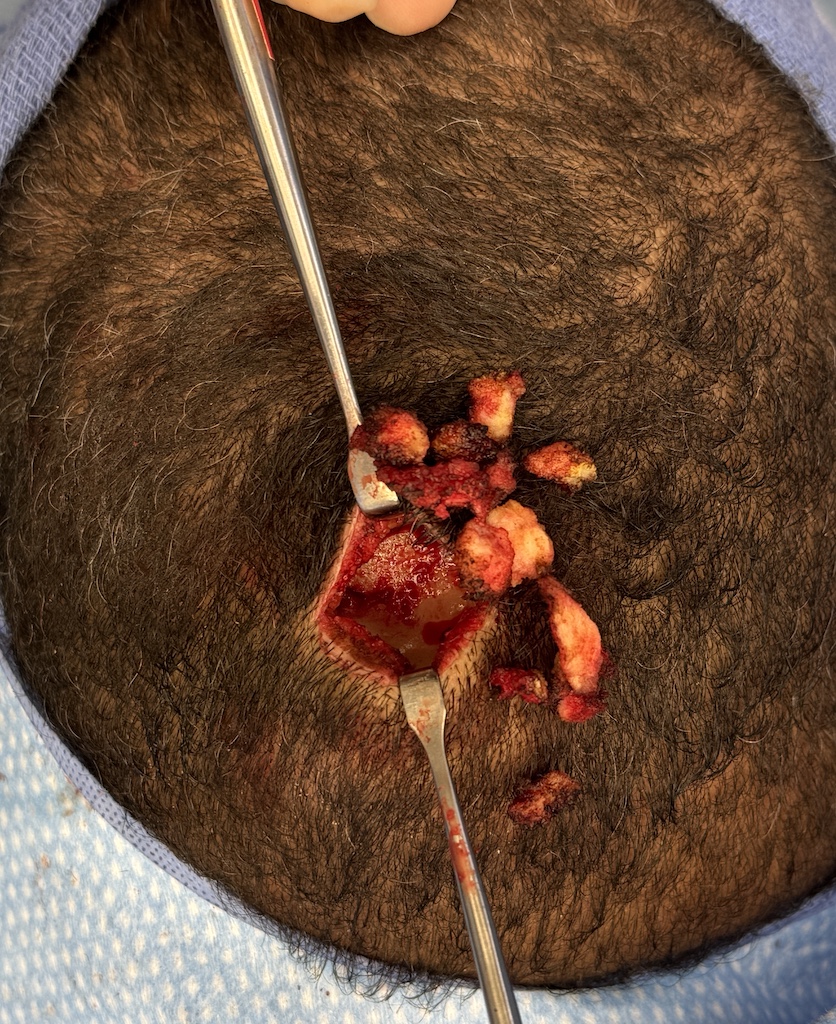

In rarer cases, however, the soft tissue component can be disproportionately thick. This is most often seen in patients with darker skin pigmentation, as the posterior scalp is the thickest area of the scalp overall. At the junction between the skull and upper neck, excessive soft tissue overlying the occipital knob may contribute significantly to the deformity.

Case Study

This male patient had long been self-conscious about a bump on the back of his head. On exam, the prominence felt primarily bony, consistent with a classic occipital knob.

Discussion

The occipital knob deformity is typically a bone-dominant condition with secondary soft tissue excess. In this case, however, the reverse was true: the fibrotic and unusually thick soft tissue contributed more to the deformity than the bone itself.

Regardless of etiology—bony, soft tissue, or combined—occipital knob protrusions can be effectively corrected with targeted reduction techniques.

Key Points

- The occipital knob deformity may arise from excess bone, soft tissue, or both.

- In soft tissue–dominant cases, wide excision of galeal and deeper soft tissues is necessary to adequately expose and reduce the underlying bony prominence.

- Even when both bone and soft tissue are addressed, the use of drains is not required.

Dr. Barry Eppley

World-Renowned Plastic Surgeon