Skull reconstruction in young children is almost always done by bone reshaping operations. For common craniofacial deformities like numerous forms of craniosynostosis, the deformed bones are removed and put back in a reshaped fashion to allow for brain growth to continue to mold the developing skull shape. But once the child reaches several years of age treating many skull shape issues is beyond what bone reshaping can reliably do both technically and risk-wise.

This issue of what to do with abnormal skull shape issues, either unoperated on or persistent issues after reconstruction, has always been a bit of a dilemma. In essence how to treat skull contour issues that can not or do not justify a craniotomy and bone reshaping approach. Ideally one would want to use bone grafts but they are both unreliable as a contour method and require a harvest site.

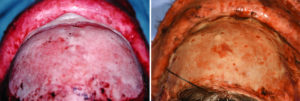

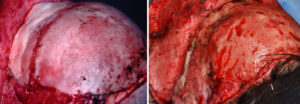

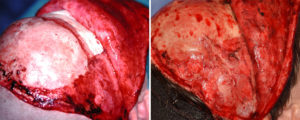

I have used hydroxyapatite cement in children as a cranial contouring materials now for almost two decades. I have found it to be very useful as skull contouring technique and have never seen a single postoperative problem develop from its use. My original animal studies from way back in 1996 showed that bone started to develop growth along the sides of the material in less than three months after its application. But there has always been the unknown issue of what is its fate decades later and does it in any way cause skull growth issues? The assumption has been that it becomes surrounded by natural bony overgrowth and grows along with the surrounding bone.

While I did not dig into the original implanted site to know for sure, I would think the cement had developed bony overgrowth rather than was replaced by bone. At the least this shows that hydroxyapatite cement in growing children’s skulls appear to be very well tolerated without any adverse growth or bone effects. While this is just a single case observation it does support my original assumption about the long-term fate of hydroxyapatite cements when used as an onlay contouring material in growing skull sites.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana