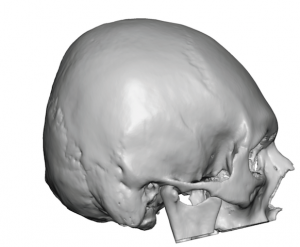

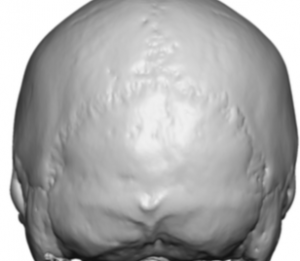

Background: Flatness of the back of the head is the most frequently seen aesthetic skull deficiency. Since the back of the head is laid on or against since early in development during the formative time of skull development, this is not a a surprise. There are many manifestations of flat areas on the back of the head from asymmetric flat areas that occur in plagiocephaly, crown deficiencies up high to more central flat areas.

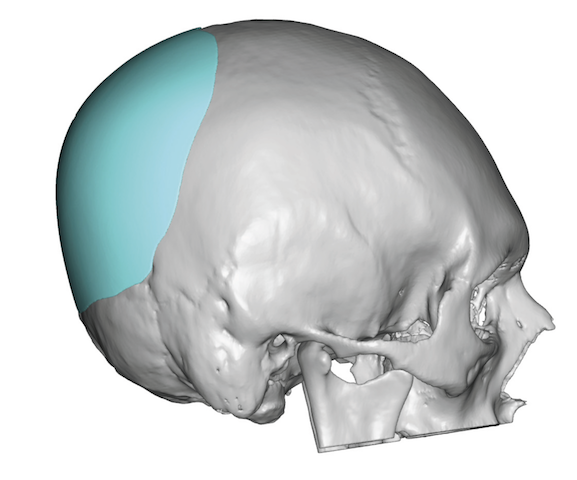

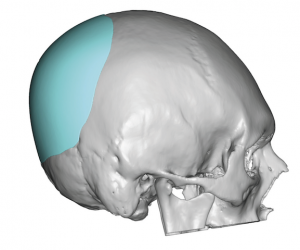

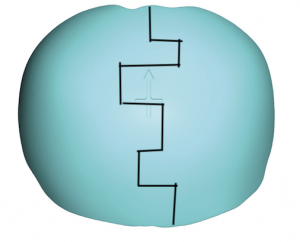

Different methods of augmentation of the back of the head exist but the most effective is the custom skull implant made from the patient’s 3D CT scan. The solid but flexible silicone skull implant permits its placement through the smallest possible scalp incision, provides the most accurate contour and fit for the desired augmentation effect and is provides ease of reversibility or exchange if a different implant is desired.

Given that the implant is on the back of the head, frequent questions are asked about its ability to move, migrate or be able to resist traumatic impacts. Since silicone elastomers can not fracture they are completely impact resistant. In some ways it is like putting a bumper on the back of your head. They are also no known in my experience to migrate or move after placement. It is hard enough to get them to fit under the tight scalp where postoperative movement is ever unlikely. Between screw fixation and the placement of perfusion holes in the implant which permits tissue ingrowth, implant migration seems virtual impossible.

Another not uncommon question is whether wearing a helmet would in any way cause an implant problem. This has been an occasional question from a patient who has to wear a hard hat for their work after the surgery. My answer has always been the same…I don’t think it ever would since such a helmet is static in position.But a new variation on the helmet question is what about the football player who wears a helmet which is exposed to impact and shearing stresses of the scalp over the implant…

With so many perfusion holes in the implant this seems to be the best method to resist any excessive shearing forces imposed on the scalp from a football helmet.

Case Highlights:

1) A back of the head that lacks projection/roundness will appear flat, like a section of the skull is missing.

2) A custom back of the head skull implant can be designed that provides pure horizontal projection only.

3) In a patient who will play football after the surgery where a helmet will be worn that is exposed to traumatic shearing forces, plentiful perfusion holes in the implant should be used.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana