Background: Cheek augmentation is a common form of aesthetic midface enhancement and uses standard implant styles and sizes to do so. While effective in the properly selected patient, standard cheek implants are inadequate for cheek deficiencies that are more significant in scope, when cheek asymmetry exists or when a specific cheek look is desired. (e.g., high cheekbone look)

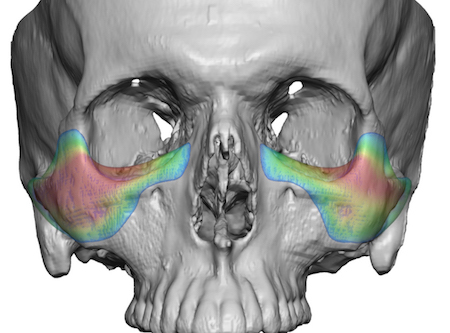

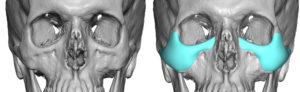

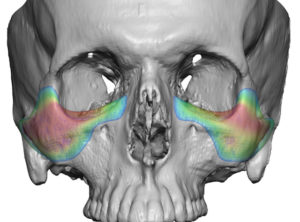

Because the eye socket is connected to the cheek bone by both development and anatomic proximity, certain types of cheek deficiencies involve both midface bones. This is most typically seen by the patient as having shallow undereyes or infraorbital hollowing. It is also known as a negative orbital vector. All of which means the anterior position of the bony infraorbital rim and anterior cheek are recessed. With this type of facial skeletal deficiency, the infraornital-malar bony complex needs to be treated for a satisfactory augmentative effect. This can only be done by a custom implant design.

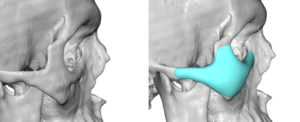

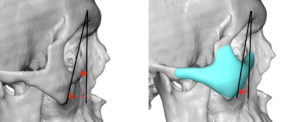

The placement of custom infraorbital-malar implants that have a significant infraorbital component almost always needs to be placed from a lower eyelid approach. It is common to look at the length of these implants vs that of the incision and feel that the implant will not fit through it. But it is really no different than looking at an anatomic chin implant and a small submental skin incision where one can have the same impression. In reality it is not the length of the implant that poses a limitation but its thickness and height that may.

Case Highlights:

1) Significant infraorbital-malar flattening requires a custom implant design that vertical raises the infraorbital rim as well as augmentation out along the zygomatic arch.

2) Such a large infraorbital-malar implant can the placed through a lower eyelid incision in a geometric split method.

3) Reassmbly of the implant can be done once past the eyelid incision and aligned and secured in place with screws.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana