The introduction of hydroxyapatite bone cements (HAC) in the 1990s, based upon an extensive experimental and clinical history of proven osteoconductive responses in maxillofacial surgery as granules and blocks in the 1980s, was a welcome alternative to acrylic (methyl methacrylate) in cranioplasty and skull augmentations.The ability to intraoperatively mix and mold a liquid and powder composite offers a tremendous advantage in shaping and customizing the augmentation..

Despite these advantages, historic HAC formulations have been hindered by prolonged intraoperative set times. Improved HAC formulations have improved upon these set times by using a weakly acidic solvent which increases the rate at which the powders go into solution, dropping set times into the 10 minute range. Further improvements in HAC, however, in set times would be even more preferred.

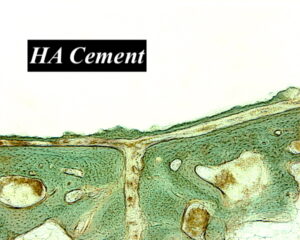

The resultant HAC crystalline preparations have very limited porosity and fibrovascular ingrowth and subsequent bone replacement is largely theoretical and virtually non-existant, particularly in mature bone. Any tissue ingrowth that does exist most likely is along any of the fissures or cracks that may occur during setting. Reports of bony replacement with these hydroxyapatite materials has been largely in long bone animal models. The bony behavior in the medullary canal of a functionally-loaded long bone is vastly different from a craniofacial site and a similar biologic response should not be expected.

Regardless of the set times, all forms of hydroxyapatite cements for skull contouring require an open field for adequate application and creation of a smooth outer shape. They are also very sensitive to moisture so any bleeding points mist be controlled before application. If not the cement will not set properly.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana