Background: Aesthetic skull augmentations by the placement of an onlay material has a relatively short clinical history. The original skull augmentation material was PMMA bone cement which was borrowed from its much more common use in orthopedic surgery. As it name implies it is used as a cement by which joint replacements are secured into their intrabony locations. When applied as a skull augmentation material it does not bond to the bone as its name implies but does serve as a shapeable material that can be used to extend the outer contour of the skull bone.

The favorable material feature of PMMA as a skull augmentation material is its capability to be intraoperatively shaped. By combining powder and a liquid monomer a putty-like material is created which has a time period in which it can be shaped until it cures/hardens. While initially used as a bone replacement material in neurosurgery with a wide open exposure has evolved into aesthetic skull augmentation methods by which it is introduced through very small scalp incisions. It passes through the scalp incision in its putty shape and then is shaped externally by molding of the scalp until it becomes hard.

This small incisional placement method is an effective aesthetic use of the PMMA material but it has one flaw….how is the material explanted if the patient wants it removed or modified? The PMMA is a hard implant which is far bigger than the incision through which it was placed in a different physical form. The obvious answer is to just make the incision a whole lot bigger to do so. But for aesthetic reasons this is not a appealing choice.

Case Study: This male had a history of a prior PMMA skull augmentation for a flat upper back of his head in Korea. While he had an excellent contour result with no visible edging he wanted it removed as the concept of having a synthetic material on his head was unnerving. He went to another surgeon in the US who took him to surgery but was unable to remove it.

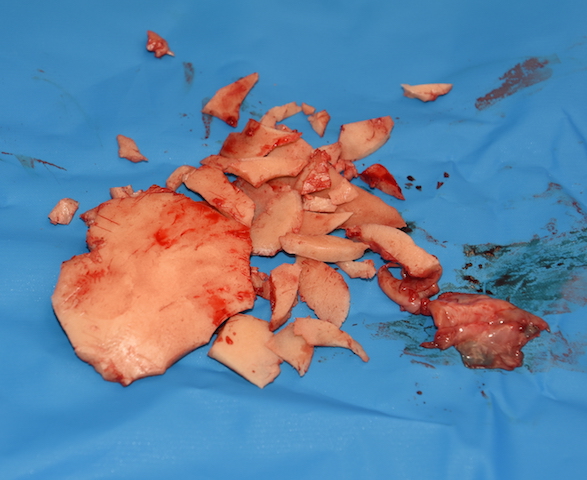

While PMMA is a hard material when cured, it is somewhat brittle when it becomes thin enough. Since skull augmentations have to have a smooth edge to blend into the bone there are very thin around the outer edges. This is a good place to begin the fragmentation process so the ‘ship can be removed from the bottle’

Case Highlights:

1) Bone cement skull augmentations work on the principle of insertion through a small incision with external molding to create its shape as it cures. (hardens)

2) Getting PMMA bone cement skull augmentations out through the same scalp incision poses a challenge as the hardened implant is much bigger in diameter than the incision through which it was placed.

3) The spiral fracture technique is a good method to sequentially make the PMMA cement implant smaller until its diameter is less than the width of the scalp incision.

Dr. Barry Eppley

Indianapolis, Indiana